Donald Trump ,the candidate, was nearly unbelievable to many Americans. He was the winner of the party nomination without assembling a large grass roots organization, without being specific about how he would change things, and had not raised much money nor spent much on advertising. And, he was not a professional politician, not a source of new ideas and new programs for fixing the nation’s problems, and not easily categorized by the usual labels we put on politicians. Where did he come from, and why was he been politically successful without behaving in the way we expect successful politicians to behave? The reality show of his convention and the campaign, was not traditional, but extremely popular to many Americans, and highly troubling to others. What’s going on?

Trump, or someone like him, is a product of the times. In the ‘good old days’ the candidates tweaked the traditional messaging of their party, and won by demonstrating good looks and charisma, by spending political capital earned by long experience producing favors for other politicians, by having superior fundraising and organizational skills, and sometimes even by the subtleties of their message itself. But why Trump?

My thesis is that he has successfully channeled the anger, and overwhelming economic frustration that has risen up in America. Americans understand that traditional messaging of politicians about incremental changes to try to improve the lot of their voting base: a bit more added to the minimum wages, promising to lower taxes, or provide somewhat bigger defense budgets, cleaner water or air, abortion rights, even Supreme court composition— these incremental political issues didn’t cut the mustard for candidates on the political stump this year.

For too many many American families “it’s the economy, stupid”: economic opportunity isn’t what it has been, or what was hoped for. Jobs have disappeared, and prospects of new ones are not evident.This is a serious catastrophy that has been growing. This isn’t about economic policy and slower-than-expected economic growth. This is about people not having jobs. And, its about no prospects for children being able to afford to stay out of labor markets long enough to go to college and emerge into promising careers.This is about much of what we used to consider the “middle class” sinking into a sea of lost hope and growing stress; its the world of continuous high stress, well known to the nation’s poor.

This situation has been emerging for a while, but politicians haven’t done anything about fixing it. For the afflicted, the problem needs bold, out of the box, and immediate attention. And, yet when all of us look around, what these people see is that some Americans appear to be doing well, earning preposterous salaries, and showcasing their wealth on TV for all to see. And, the incidence of this core economic plight has been growing in America, creating deep anger and bitterness. Politicians have, of course, been exploiting this, as politicians will do— reminding people about their plight, and pointing their finger at their opponents to place the blame (eg the theme of the speech by Michael Douglas in The American President) But Trump has put the pieces together and is positioned well for channeling the anger so effectively: by being the outsider (not the insider and part of the problem) and being the the “bold business decision-maker” (to step up to the big problems and opportunities that confront America). He has also been able to depict Obama & Hillary Clinton and his understudy as the indecisive, dangerous, cronies of vested interests that wont step up to the real issues. And, to be sure, Mr. Trump said nothing about “how” he might tackle the jobs and income security problems we face. He has not had to be specific.He has flooded the media with evidence that he both understands the deep angers of the people, and has the brash outsider style that suggests that he may well be able to take remedial action. He is the candidate for a very troubled, and for a troubling time in America.

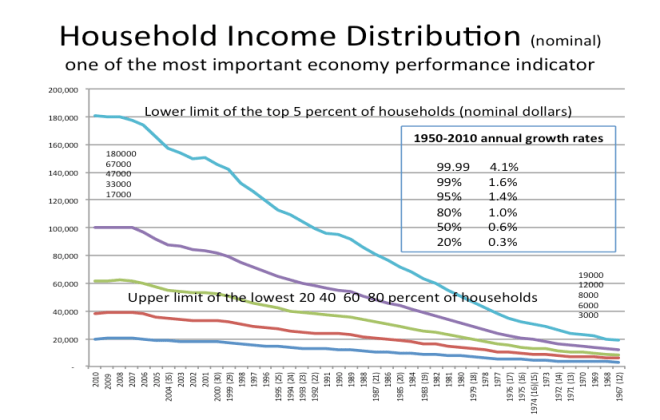

Stepping back: The income distribution in America has been changing quickly. I think this is the source of the growing anger in America and source of Mr. Trump’s appeal. The rich segments of society are growing richer at at an alarming rate, and the middle and poorer households are stuck. The politics in America are reflecting the anger over this inability to make progress, and being in the long social media shadow of people who get richer and richer. The chart below shows the growth rates for segments of the income distribution. Overall, four of five people have experience income growth over the past two generations of less than 1% a year. And, at the same time the highest earning americans have seen incomes rise faster, with the rate of increase being higher, the higher the income. The inability of most struggling families to experience opportunity for their children is made even more difficult by the public displays of wealth and extravagant consumption in the media.

The problem with income distribution reminds us that the way people end up sharing in the economic pie in a market system is through their participation in the labor market— earning wages for their work. This labor force participation is, for the most part, the way people get their tickets to the products and services produced by the market economy. Lots of good thinkers have suggested that this is exactly what is wrong (inequitable) about a market economy. Offsetting this, here in America, is the well documented view that capitalism is the way to grow the economic pie faster and bigger than the non-market alternatives. Progress can be fast in a market system. But, we leave behind sometimes quite large groups of displaced workers (witness Detroit and the rust belt cities, or Lowell/Lawrence).

One of the implications of the widened gap in income inequity is shown in the following chart— a picture of the “American Dream” of having one’s children have a better. or more successful life’

The “dream” has been slipping away as so many of the middle and lower class household are unable to see their children have a higher income than they have had.

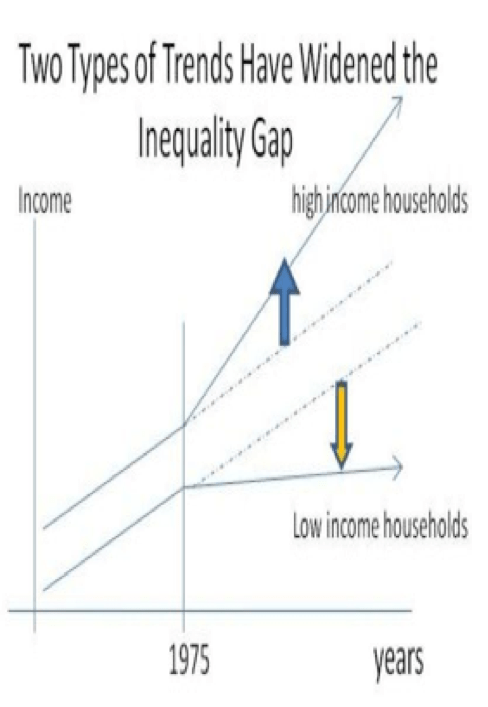

Here in America the trends in progress over the past 150 years or so have differentially affected labor markets, with knowledge and skill related jobs being created, and with manual and low skill jobs being eliminated. What this does is to cause “shortages” in the high skill jobs and “surpluses” in the low other skilled jobs. Or, rising wages in the former and falling or flat wages in the latter.

What caused the trend? Lots of things cause progress in the economy: Invention (cotton gin, wireless communication), innovation (Henry Ford, the Internet), scientific progress (longer life spans and human genome), discovery (oil and minerals), and capitalizing on foreign trade and comparative advantage.

This trend in “progress” creates winners and losers in the economy. Every time changes occur in the flow of goods and services as a result of “progress” some new jobs are created and old ones disappear. This has been going on since the beginning of mercantilism, and the pace is speeding up. Look at the graph below that characterizes trends since the Vietnam era. The upper income groups seem to be capitalizing on progress, and the low wage earners seem to be disadvantaged. Two things of note about this trends in the impact of progress; (1) this is a growing source of the anger we see in our society. The lower income groups are living in a world that seems to not have economic opportunity, and their low skill jobs are being lost. And, it an intergenerational problem— as the rich get richer the poor (and their children) do not. (2) this didn’t start with President Obama and the new trade agreements, or lack of border control. Its been going on a very very long time. And, little of it has anything to do with Presidential authority and policy. It is about the changes in the economy and job structures that arise when scientists do their thing, when entrepreneurs do their thing, when innovators do their thing, and when consumers looking for better bargains do their thing.

This “progress” drives a wedge into labor markets and the income distribution, at least temporarily. Then, as people adjust, it resolves. The problem is that it may take generations to resolve, and may involve families moving long distances to find better jobs (and loss of family ties), investments in college educations, smaller families to match smaller incomes, and other disruptive things. But, in the labor markets, we still find upward pressures on higher paying jobs, where progress stretches the supply of qualified labor. And, soft labor markets at the low wage level, where progress is always working to displace jobs and create added supplies of workers in other continuing low wage jobs. — tending to suppress wage increases in the low wage jobs.As depicted here, the ‘wedge’ between high paying jobs and lower paying ones have contributed to the income distribution trends.

The disturbing trends in the distribution of labor (rich getting richer, and the poor not getting richer) are caused by “progress”, or technologic changes and innovation including things like outsourcing supply (brought on by free trade, cheaper transportation technologies), inventions and disruptive innovation (like the internet and Amazon, mall shopping, assembly line production, electrification, robotics, etc.) and several other more modest influences like Labor force participation of women going up when birth spacing became reliable. Yes, immigration of unskilled and language-challenged persons may make this wage “gap” problem worse(though the immigration of highly skilled and educated persons will ease the upward pressure on wages at the upper level).

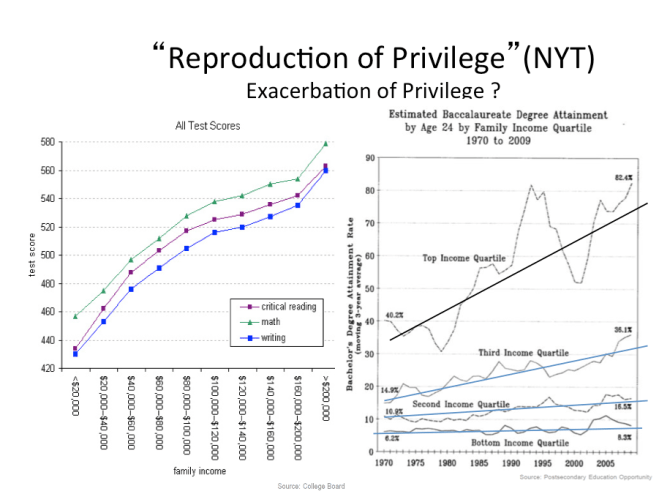

The disturbing trends in income distribution are exacerbated by the trends in education across income groups. This interesting piece shown below from the New York Times is quite depressing. The chart on the right below shows the trend in the % of children receiving a college degree, by income group. It is alarmingly like the income distribution chart— alarming, but not unrelated. The income distribution is something parents pass along to their children. It is an intergenerational legacy ! (in spite of the talk of opportunity). The chart on the left shows how the legacy is, in part, executed. It shows the student college entrance exam score—and how they are correlated with income. This pattern stems from the way we fund K-12 education in America…. By using property taxes. Poor communities generally have poorer schools, richer communities have better schools.

The only way to “have our cake and eat it too” (get progress without the disturbing impact on the distribution of labor) is to make it possible to make the labor market adjustments to “progress” more quickly. To make it possible for displaced low skilled workers to transition more quickly to other useful jobs. And, to allow the new forms of high end jobs that will need to be filled to be filled faster! This could happen by:

- raise the levels of formal education

- provide incentives for employers to provide job training for newly needed workers, and for workers being displaced. (this might also create a demand for new vocational educational organizations in the U.S.)

- provide new bridging public works programs (probably at the community or state level) to provide jobs for chronically unemployed persons. this is like the jobs programs during the great depression (building roads, parks, dams for water control, and other things).

A Human Capital Theory of Demand for Household Investments in Education and Health

The theory of Human capital (G. Becker) provides a basis for understanding how people make decisions about using time and money to make investments in future well being. Specifically, we are thinking about the demand for education, the demand for health, and the demand for relocation. Unfortunately, the theory may explain some of the systematic failures of poor people from making these kind of investments.

When we think about “demand theory” we are usually thinking about people deciding whether to buy goods or services (and expend shopping time) based upon the incremental benefits of consumption, and the incremental requirements of time and money. This kind of decision calculus doesn’t really apply to directly to decisions when the benefits or costs are spread over future time periods.

Lets say we are looking at the decision to invest in a single evening course, which will create a skill that allows wages to be higher going forward. The decision would involve the costs of the course: foregone benefits of using time as well as the money costs. And, the benefits would presumably come in the form of higher wages in the future. For simplicity, the costs of the course are incurred in the current period. The benefits of higher wages would be spread over all future years. The decision might be framed as:

Course costs = W1 – Wo + W2 – Wo + W3 – Wo + ….. + Wn – Wo including time _________ ________ ________ ________

(1+i)1 (1+i)2 (1+i)3 (1+i)n

where i is a discount rate reflecting the person’s time value of money, and the exponent for the discount factor is shown following the parentheses. What this says is that the future wage benefits, whatever they are, become less and less important as the occur further and further into the future.

Why does money (or any benefit) have a lower value when it occurs in the future? Well, lets say someone owes you a dollar. They ask if you would prefer to have the dollar repaid now, or a year from now. You would always prefer it now, because you could always do something with it now (like put it in the bank) and it would be worth 1.02 or 1.03 or much more a year from now depending what you do with your choices. The value of money depends on when you get it —- the value is greatest now, and the value declines the longer you have to wait.

The time value of money is going to be different across people. The general form of the equation shows the time value of money represented by a discount rate (i). The time value of money is larger, the larger the discount rate. If the discount rate is large, say 10%, then the value of future benefits falls very very quickly off into the future. The benefits at the end of year 1 are worth on 90% of the nominal amount to be paid. But after 2 years, the discount is (1.1 x 1.1 = 1.21) or 79% of the annual benefit. After three years it is 67% and it continues to decline. On the other hand the stream of benefits valued in current dollar terms declines very slowly if we use a discount rate of 2% ( at the end of year 1 –98%, year 2 — 96%, year 3 — 94%, year 4 — 91.8%, and so on. The degree of time preference is described by the discount rate: persons with a strong preference for “living in the moment” will not value the future benefits highly– they will have very large discount rates. People who are always thinking about the future, and planning for it —- value the future benefits more —- and have lower discount rates.

So, in theory, we can think of 2 people. Person has lives pretty much in the moment—- sees little benefit in postponing benefits until tomorrow. The stream of 7 years of higher wages for taking a course is shown as person A. The discount rate for this person is 10%. The other person (B) has a discount rate of 2%:

Model 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

10 year stream of Benefits A 90% 79% 66.9% 55.6% 39% 23.8% 5.2%

10 year stream of Benefits B 98% 96% 93.9% 91.8% 89.6% 87.4 85.2%

So, for Person A, the benefits associated with waiting 7 years are virtually nil — 95% of the value is gone if we have to wait 7 years. While, for person B after 7 years there is still considerable value in waiting 7 years to get benefits.

So what’s the point? People are different. Waiting or postponing benefits is not something that creates a good stream of future benefits for Person A, but it may interest Person B.

So what about choosing to make educational investments? Young people will make different choices about getting a college degree:

- some will perceive a higher opportunity cost of not working (or working less) than others —- other things the same, these people will not attend at the same rate

- some will perceive more urgency in time preferences than others (a higher discount rate) —- other things the same, these people will not attend at the same rate

Unfortunately, these differences are not just randomly scattered across all high school graduates.

So what about choosing to make Health investments? Some benefits of healthy living (eating well, exercising, etc.) may yield current “feeling better” benefits. Other benefits, of course, may not appear until later in life. So, the benefits for health investments may be seen as short term and others long term. The long term benefits at the point of decision are going to be worth far less to persons with high discount rates than for other persons.

So, what might contribute to differentials in time preferences across socioeconomic groups? Where does “investment” make sense, and where doesnt it make sense? In the case of poor persons there may not be much opportunity to wait. When you dont know how or if a meal is going to be on the table tonight or not, it would be easy to conclude that discount rates regarding future benefits are going to be very high. Urgency rules. Planning, patience, investments, and future returns all may pale in the unmet needs of the moment. Investments in education just don’t look good because the benefits are well over the horizon, and seem not worth much from todays vantage point. In spite of comparability of other costs and benefits in the model 1 earlier, the difference in the time preferences (discount rates) will make the health investment look less attractive for person A than person B. And, person A, the the high discount rates, may have such time preferences because of the urgency of poverty. Health investments by poor families may just not make economic sense.

Educational investments are similar. This situation, if true, is problematic, because the avenue out of poverty for families may well involve educational investments of money (opportunity cost) and time. This may help explain the why the income distribution is so sticky for the poorest Americans, and why the ” reproduction of privilege ” piece notes the very poor educational attainment of the poorest young people. So, if the urgency of life creates a view of time (present vs future) that is different for the poor than it is for others, then the demand for education my be suppressed because the stream of future benefits is weighted much lower in value than for a comparable middle class person.

Changing the Social Contract?

The way society produces and shares its yield with the people is the “social contract”. As we noted earlier, the market system has a social contract that says: from each according to ability, to each according to ability! The Socialist view was “from each according to ability, to each according to need”. The income distribution is at the heart of this dispute. The incentives generated in markets and labor markets (do more, do it better, and you get to consume more) help grow the pie faster, but they are definitely creating a problem in America.

What’s the problem. Two class societies have existed throughout history. Haves, and have nots. Why not just let the trend go on? In a word—violence. The political consequences of the anger that is generated by the unequal distribution of income and wealth will create political disequilibrium. Count on it. History is pretty clear on this cause-effect consequence—and ironically, American foreign policy proclaims that the worlds people have a right to democracy (self governance) and to overthrow regimes that protect wealth for a selected class by having some dictator, monarchy, or military rule. Look at the Russian and French revolutions, what happened in Iran, Iraq, the Arab spring, Cuba, and other places. Angry people will revolt. They are revolting today–the ‘lone wolf’ terrorists in America are not so simply a “muslim” problem. This is pent up anger being vented. People completely trapped and frustrated by society, people with no hope. There are millions of them in America. Most will turn to drugs to numb their anger. Many will cope. Some will turn to violence.

Our angry right politicians are simply capitalizing on pent up anger by the left behind segments, pointing fingers at immigration, on muslims, on the the IRS, on government in general, on Obama and Hillary. Violence by angry and frustrated Individuals will growingly be in the news. This isn’t a pretty picture. 50 years ago many of this middle/lower class were called “the silent majority” (eg middle class workers and taxpayers). Whatever we call them, they aren’t going to stay silent. We should worry that the violence that is emerging will create political instability, and shut down a functioning government. Somehow, this seems to be the direction we are going. Somehow, we must redirect the anger.

The social contract needs to be rewritten. The number of jobs is not growing as fast as the number of people.Technology will continue to steepen this trend. Robotics is still a small symptom of the influence technology is going to have on jobs and the necessary size of the labor force. And, the price of higher education will continue to rise, shutting down the demand, one of the most important vehicles for creating an avenue for displaced workers and their children.

In spite of fantasies about “the good old days, where good manufacturing jobs existed to propel millions of families into the middle class, jobs are, becoming less useful a tool for allocating the product of our economy. Milton Friedman proposed an answer 50 years ago–the negative income tax. It wouldn’t be any more popular today than it was then. Or, we could adopt a solution adopted by President FDR in the 1930’s to put America back to work: the large scale government employment programs (including service). This wouldn’t be popular now either. Trump proposed to shut down trade agreements that cost jobs. As a high wage country, trade agreements are almost always going to cost jobs in America in order that we can specialize in our comparative advantages of technology and services–and so we can reap the gains of letting our trading partners specialize in making things that use lots of cheap labor. Better trade deals (or no trade) is a solution that may keep more jobs at home, but it will certainly shrink our economic pie. How much would it cost to revert to economic isolationism? 5% of GDP, 10%?

All of these solutions are problematic and divisive. What are we to do to provide hope for the economically hopeless? To redirect the anger, and the violence it produces?